In this chapter, we'll leave IEx behind and start writing our first real Elixir application!

Using Mix

When you installed Elixir in the first chapter, you also got a little command line program called "Mix". The mix bash command lets you do many things, like installing third party libraries, generating files, testing your program, and much more. If you've ever used Ruby, you could see mix as a combination of bundler, rake and gem -- all combined into a single powerful command!

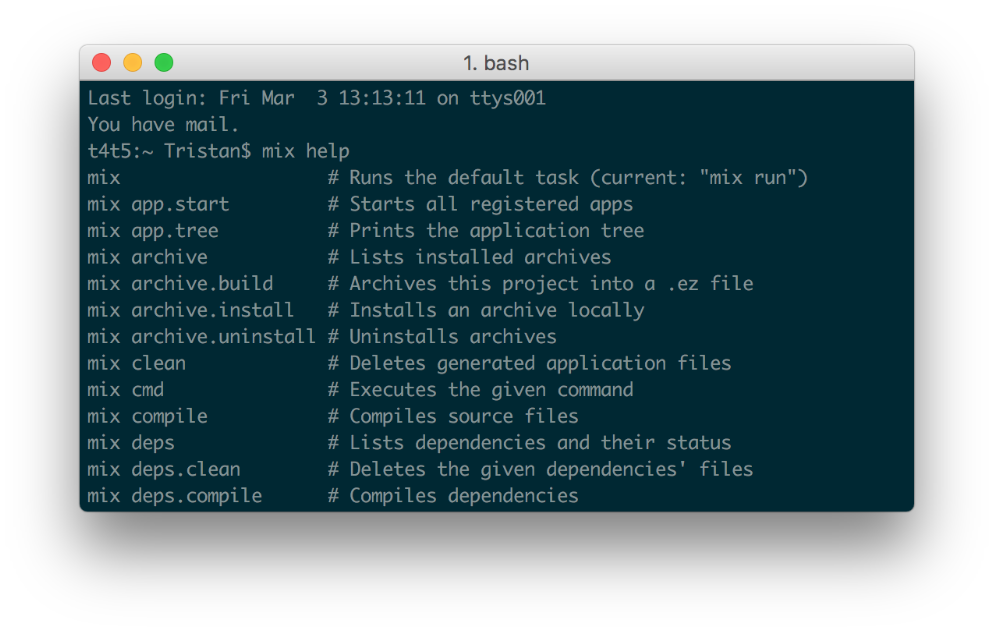

Pro tip: when in doubt, you can type mix help to see a list of available commands:

Alright! Let's use Mix to create an Elixir application called elixirapp:

$ mix new elixirappYou should now have a new folder called elixirapp that you can cd into:

$ cd elixirappWhat's in a project?

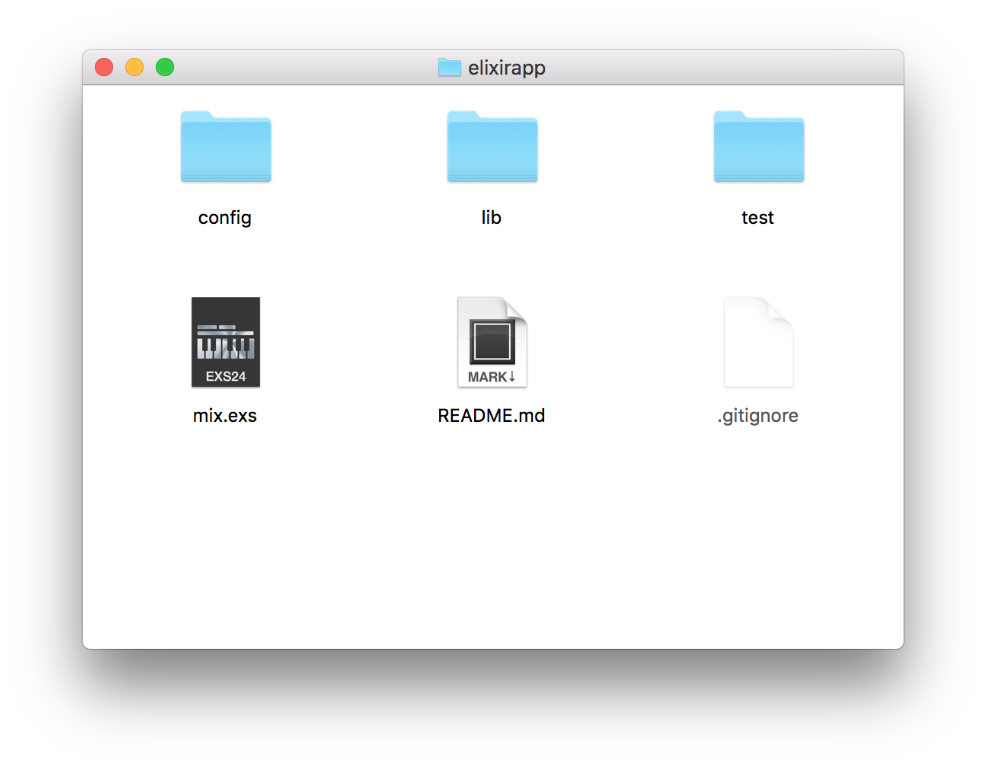

Inside your application's folder, you should see the following files and folders:

Let's go through them one by one:

-

config: sets configuration details for your app. Right now it only contains a single file (config.exs), which sets configurations that are common across all environments. In the future you'll probably want separate files for each environments (e.g.prod.exsandtest.exs). -

lib: this is where your app lives and where you'll write the vast majority of your Elixir code. Right now it only contains a single file --elixirapp.exwith an empty module. -

test: the home of your automated** tests**, which exist to make sure that your app is bug-free. The filetest_helper.exsis executed before any other test file. Note that all your test files must end in_test.exs, just like the default file:elixirapp_test.exs. -

mix.exs: if you've ever used Node.js, you'll notice that this file is roughly equivalent topackage.json. It's used to define version numbers, both for the app itself and for its dependencies. -

README.md: a simple Markdown file where you describe how your apps work.

Now that you know the basic file structure of a Mix project, let's write some code!

Writing and running your code

Let's start with a good ol' "Hello World"-application! Open the file lib/elixirapp.ex and create a function called say_hello using def:

# lib/elixirapp.ex

defmodule Elixirapp do

def say_hello do

IO.puts "Hello world!"

end

endSave your file and open the command line. Make sure that you're in your program's folder and run this command:

$ iex -S mixThis will compile your entire Mix application and open it in IEx. Now you can call your application's functions by referencing the Elixirapp-module:

iex(1)> Elixirapp.say_hello()

Hello world!

:okReading the user's input

Let's make our program a little more interesting. We want to ask the user what their name is, read their input, and then print out "Hello (whatever their name is)". If the user doesn't fill in their name and tries to continue, the application should show an error message and ask again.

We'll start by building a main-function where we read the user's input through IO.gets and inspect it with IO.inspect. We'll leave our previous say_hello-function as it is for now.

# lib/elixirapp.ex

defmodule Elixirapp do

def main() do

name = IO.gets("What is your name? ")

IO.inspect(name)

end

def say_hello() do

# ...Let's run this again with iex -S mix. This time, we call Elixirapp.main, type "test" and press enter:

iex(1)> Elixirapp.main

What is your name? test

"test\n"As you can see, IO.gets appends a newline character at the end of our input. We want to trim this away before inspecting the value. To do this, we can use Elixir's built-in String.strip-function, and change our program a bit:

# lib/elixirapp.ex

def main() do

name = IO.gets("What is your name? ")

name = String.strip(name)

IO.inspect(name)

endNow, if we exit IEx and re-run the program, the newline character will be gone:

iex(1)> Elixirapp.main

What is your name? test

"test"The Pipe Operator

The pipe operator |> is a great feature in Elixir that makes your code shorter and more readable. It allows us to rewrite the following code...

name = IO.gets("What is your name? ")

name = String.strip(name)...into a single line like this:

name = IO.gets("What is your name? ") |> String.stripThe pipe operator takes the returned value of the function on the left hand side (IO.gets) and sends it as the first parameter to the function on the right hand side (String.strip). It's essentially a more readable version of this:

name = String.strip(IO.gets("What is your name? "))The pipe operator is especially helpful when you have many nested functions. Compare the readability of these two lines performing the same thing:

test = my_function(other_function(foo(bar())))

test = bar |> foo |> other_function |> my_functionPattern matching functions

Let's go back to our app! The last thing we want to do is print out the user's name or show an error message depending on the input we receive.

We'll start by modifying our current say_hello-function so that it can take a name parameter, and use some string interpolation to display it in a sentence:

# lib/elixirapp.ex

def say_hello(name) do

IO.puts "Hello #{name}!"

endNow, how do we handle the use case where the user types in nothing, and sends us an empty string? We could use a case inside say_hello, but I want to show something cooler: pattern matching functions!

Above our current say_hello-function, we can declare another, seemingly identical, say_hello-function, but where the difference is that its first parameter is always an empty string. Inside it, we log an error message and return to main():

# lib/elixirapp.ex

def say_hello("") do

IO.puts "You need to provide a name!"

main()

end

def say_hello(name) do

IO.puts "Hello #{name}!"

endNow, when we call say_hello from main, our program will run through the say_hello function declarations in our file from top to bottom and latch on to the first one that it matches with. This means that if our name variable is an empty string, it will go to the first say_hello, but in all other cases, it will go to the second one. Cool!

Our final program should now look like this:

# lib/elixirapp.ex

defmodule Elixirapp do

def main() do

name = IO.gets("What is your name? ") |> String.strip

say_hello(name)

end

def say_hello("") do

IO.puts "You need to provide a name!"

main()

end

def say_hello(name) do

IO.puts "Hello #{name}!"

end

endLet's restart IEx, run the program one last time and make sure that it works as expected!

iex(1)> Elixirapp.main

What is your name?

You need to provide a name!

What is your name? Tristan

Hello Tristan!

:okOne more thing...

Another quirky thing about Elixir is that when a function is called (and the program has to decide which function definition to latch on to) it not only pattern-matches against the values of the parameters, but also against the number of parameters itself!

In our program, we could add a third definition of the say_hello-function that takes two parameters instead of just one:

# lib/elixirapp.ex

def say_hello(greeting, name) do

IO.puts "#{greeting} #{name}!"

endThat way, if you call say_hello("Tristan") (with one parameter), it will print the usual "Hello Tristan!", but if you call say_hello("Good morning", "Tristan") (with two parameters), it will latch on to this newly defined function instead, and print "Good morning Tristan!".

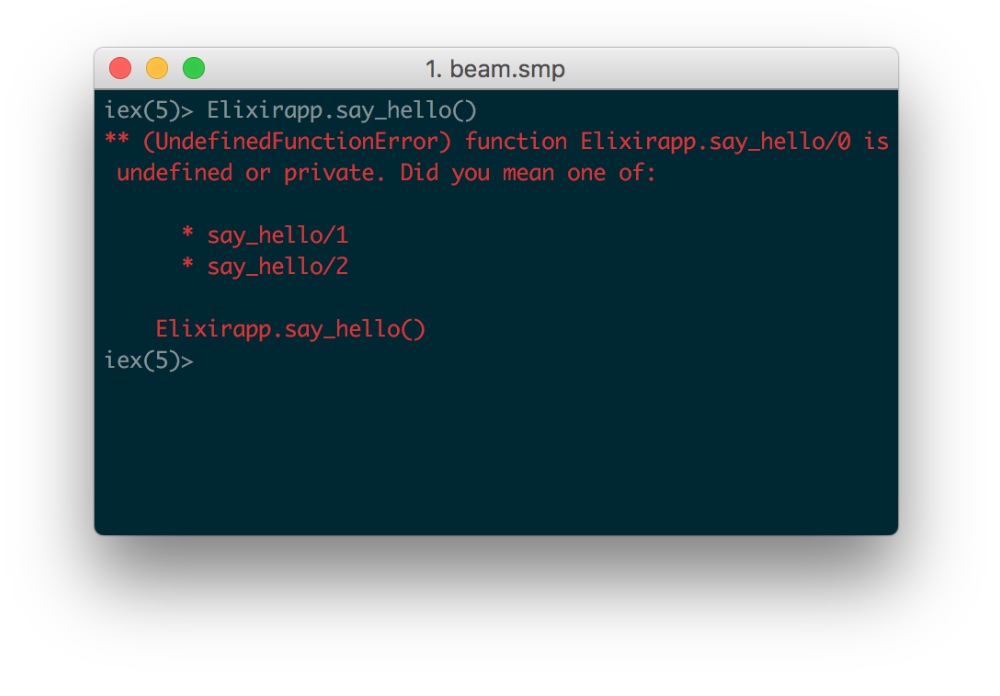

Because of this feature, Elixir programmers always **specify the number of parameters **a function takes whenever they reference it, like this: {function_name}/{number_of_params}.

For instance, in our example above, we have both say_hello/1 (which takes one argument) and say_hello/2 (which takes *two *arguments).

You'll notice that if you try to call say_hello/0 or say_hello/3, Elixir will give you an UndefinedFunctionError:

Sweet! Now you should have a basic overview of how Elixir works, including some knowledge on pattern matching and the pipe operator. In the next chapter, we're going to start diving into the Phoenix framework!